Fondly known to us as Siang, Mdm. Yueh-Siang Chang is a curator and art historian, and one of our Residential Fellows (RF) at Cinnamon College. After majoring in History at NUS, Siang pursued a curatorial path at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) and Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A). Since then, she’s served as Assistant Director for the Singapore Bicentennial Office, senior curator at Yale-NUS, and currently, as a curator for the NUS Museum. One summery afternoon, we sat down with Siang in Chatterbox for an insightful chat.

In this extensive feature, Siang shares with us her upcoming NUSC module, thoughts on being an RF, takeaways as a History major, favourite art pieces, advice for aspiring curators – and more!

By Zheng Chengzhi ’23

Hi, Siang. Could you tell us what you’re currently working on?

Many things, but more immediately, I’m working on finishing an exhibition installation at the NUS museum. Also, the semester’s coming up and I’ll be offering a module [NHS2055] with Dr. Quek Ser Hwee, so that’s what’s keeping me busy.

What’s this module about, if you don’t mind giving spoilers?

Not at all. It’s a module that considers museums and urban spaces in our heritage landscape, on an introductory level. We want to look at how decisions are made, whether in museum curation or state decisions on heritage planning. Then, we want to explore the idea of where the layperson comes in, as the participant in all of this. [We want] to give people an entry point in learning how to read museums and urban spaces, to know what they’re looking at and what those things mean.

How’s residential life in Cinnamon been for you?

I think it’s quite good leh! I’m lucky that my neighbourhood has been quite friendly, and so far, no huge problems. Yeah – nothing of moral turpitude. [laughs] I enjoy interacting with the students. They keep me young and make me forget I’m old, which might lead me to do dangerous things like over-exercising. Like, “Yeah, you still think you’re young, but actually you’re not?”

I think their music choices keep me grounded, too. When the students did that End-Of-Semester dinner, the theme was retro, but I’d never heard any of the music before. It’s like they consider a certain generation of songs retro, but for me, it doesn’t even go back to my time. [laughs]

What’s the most rewarding thing about being RF?

Before offering this course, I was the only non-academic staff on the RF team. So in that sense, I found it enjoyable that I could have regular chats with my residents who had questions about their papers and all that. I found it enriching to contribute that way. Otherwise, it’s always rewarding for me to be a friend and offer a different perspective. Because in a residential college, it’s a “you study where you live” situation, right? I think people sometimes lose some kind of perspective, where the only thing they see is academics: “If I don’t pass how?”, “If I don’t do well how?” I want to help my students achieve a good balance.

What’s your favourite museum in Singapore (excluding NUS museum)?

Off the top of my head…hmm. It’s difficult to answer because museums have different generations and focuses. But in terms of collections, I’d say I like the ACM (Asian Civilisation Museum) collection best, because it offers a lot of diversity for us to understand global cultures. And I think the current direction ACM is taking – looking at port cultures and histories – raises very interesting questions. It isn’t necessarily only about high material culture; you also have the possibility of looking into local, indigenous cultures.

My problematisation of the current approach, though, is that they have to strike that balance between something that’s potentially more intellectual, and something more interesting to the general public. At the moment, I think fashion is being used as a hook. If you look at the [better public-received ACM] exhibitions, they tend to have a fashion angle, even the recent Batik Kita exhibition. I feel it may tip the balance a little bit away, because you can’t just explain everything cultural by fashion.

So the TLDR is: I like the ACM collection, but I think there are things we can think about in terms of how the collection has been presented, for sure.

You previously majored in History at NUS. How did that lead to your journey in the art world?

I think there were two key things. Firstly, there was a module back in my time called “History of Ideas” that looked at intellectual history. I thought it was very interesting to observe the shifts in philosophies, of how people saw and thought about the world. [Secondly], when Dr Maurizio Peleggi came and offered an elective in art history, I thought that was interesting too, because you learn how to read an artwork for precisely these shifts and changes in thinking. For example: when you go to Malacca, you might think everything looks very touristy, right? And maybe you think something else looks very kitschy. But what, and why? Art history can help to explain what you are seeing, and who has put it there. That can change your understanding of [what you observe].You’ll appreciate it differently.

So that’s what made me want to be a curator: to signpost and explain artworks to people so they can enjoy it better.

Could you share more about what sparked your interest in curation?

I think every curator’s first instinct is, “I want to explain”, or “I want to share something with somebody”. And once you get more mature into [curation] and look back, you realise that it’s because at that moment in time, you didn’t understand a lot of things about the world. Yeah – you think [something] needs to be explained to people, but that’s because you don’t know enough about the world, and you don’t know that this has been explained before, already.

Once you get into curation, then you realise, okay – there are many aspects of curating. In curation, the word “cura” means “to care for”. You’re actually caring for the objects; that’s the root, foundational concept. But that act of working with collections also means you have to think of many other aspects. You’re not just storing [the objects] in a storeroom; you have to take them out for exhibitions, and that means telling a story about them. All these aspects of how you utilise or tell a story about [the] objects becomes part of the exhibitionary practice people call curating. For me, I think I was just interested [in curation], in the more basic idea of displaying artworks as a curator.

What’s a little known, or underappreciated fact about being a curator?

That there’s a lot of thought and manual labour that goes into it. Some people might think you take some artwork and hang [it] and print some small caption, and that’s an exhibition. But people don’t realise there’s a huge big ‘machinery’ behind the scenes of any museum that makes exhibitions even possible. You need art handlers and registrars that document the management of your collections, to make sure that everything is in place. People really under-appreciate exhibition officers and art handlers.

There is also some aspect of this work that AI will never be able to replace. When you are handling a 16th century vase, do you really trust a robot arm to help you place the [artwork]? We’ve all seen what automatic hotdog robots might do. [laughs] There’s a lot of things machines can do to help make our lives easier, but we cannot entirely replace everything.

What’s one of your favourite artworks or artists, and why?

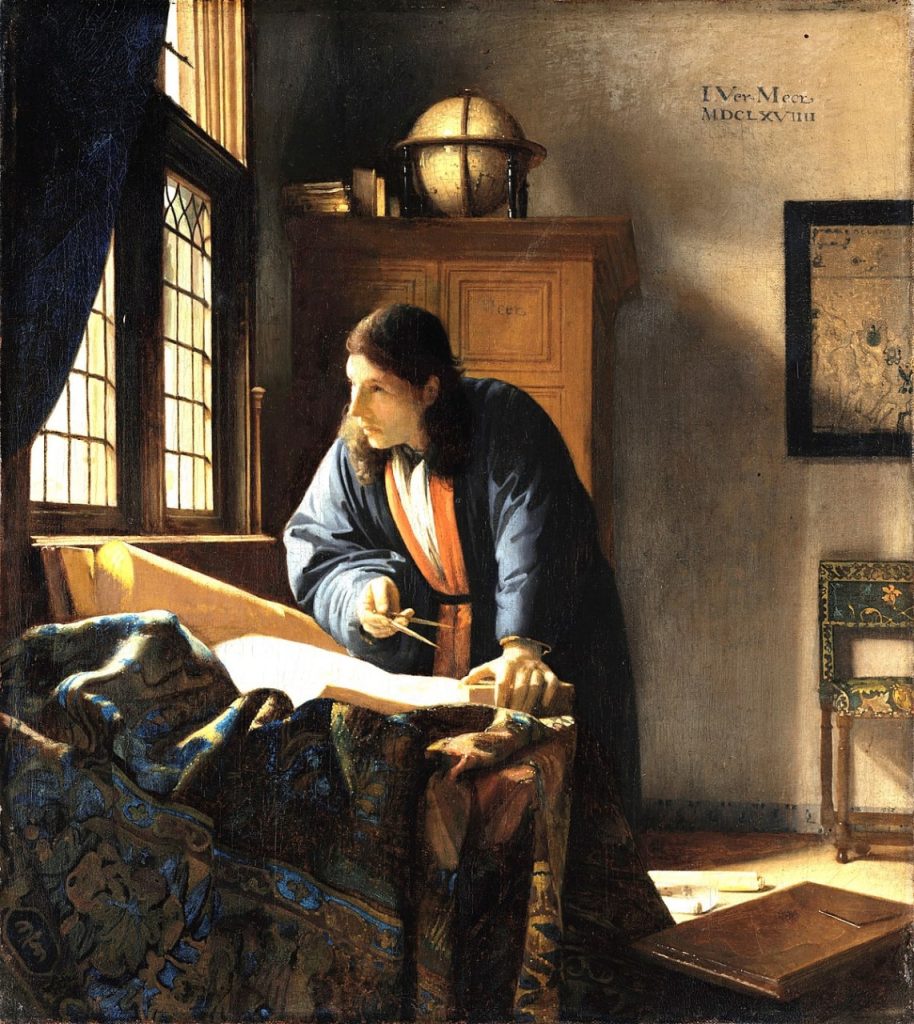

Hmm, I’m stuck with two. I like anything painted by Vermeer, but I also like the religious works of Fra Angelico, for different reasons.

Vermeer’s work is very “science and tech”. I like his painting technique, how he used the camera to bring light into his painting. And then, of course, it’s during that very interesting period of Dutch art, where there’s all sorts of hints inside the paintings to tell you about how the world was changing. But I like Fra Angelico because of the very meditative, contemplative elements in his work.

Very difficult to nail down to just one, you know!

Lastly, what advice would you give to NUSC students looking to work in the arts or curatorial scene?

When people apply for internships or jobs with me, I don’t necessarily look for the person who has chalked up a lot of relevant experience. I look for the person who has a sense of practicality. I feel that people elevate curators, you know, into these superstars. A lot of people want to be a curator because they want to tell people what to think. And [laughs] my exhibition officer colleagues will not be wrong to say that curators give a lot of problems, especially when they can’t decide where they want to place artworks ahead of time. Or when they’ve already come in and still say, “This doesn’t look right, I want to change the position”, and whatever.

I look for somebody who, in the absence of an exhibition officer or art handler, can pitch in to assist. Who thinks that, “This is not beneath me”. I look for somebody who can think on their feet, who’ll say, “Okay, we have a problem to be solved. Now, how do we solve this problem?” Several of the interns who applied for internships with me have not necessarily come from arts or history. I’ve employed somebody who was a landscape designer, because I thought, “Okay – when I’m doing this exhibition, I’d like your input on how we can design this pathway. You may not have any exhibition experience or any museum experience, but I want to learn something from you, and I think you can learn something from me.”

I understand there is some value in getting the top qualifications: postgrad in museum studies, masters in art history, etcetera. But, if somebody goes straight [to working in a museum] without any kind of hands-on practical experience, I might worry for the individual. Maybe it has to do with my own training, because where I started at the V&A (in the Assistant Curators programme), you really had to do everything foundational. You did the basic cataloguing and inventory work. When something came in, you had to accession it and do all the paperwork. You’ll know then – that so much isn’t just a matter of coming in lofty and telling your handlers and registrars what to do. Because now, you understand the ecosystem and how each species functions inside, you see.

So I would say to anybody who wants to get experience with museum work: don’t just get the credentials. Try to get the foundational things. Maybe start from collections management? A lot of people want to just straight-up be an education officer or curator. These are the brainier, and perhaps more fun activities, but I’d like to see people who can get through even the random tasks. Because in the museum, it’s janitorial. Everybody has to do everything. So I think if you have those [foundational] skills, you’ll value-add. You’ll be able to get along much better with people behind the scenes, and you’ll be able to factor those [skills] into your curating, too.

*The interview above was edited for length and clarity.